The Development of Western Luxury Fashion Industry

The Development of Western Luxury Fashion Industry: A Class Reaction to Garment Technology and the Democratization of Fashion 1850-1950.

This was originally submitted as my final paper for Columbia University’s “Technology, Work, and Capitalism: A History ” seminar. The original footnotes style is not supported on this platform. Please excuse the makeshift citations.

On May 2nd, 2016, a red carpet was rolled down the colossal staircase in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Shortly thereafter, tents were set up, press and spectators arrived along with celebrities, fashion designers, and athletes; Madonna, Tom Ford, Beyonce, and Derek Jeter were just a few of the stars to grace the carpet. The occasion was the Met Gala, or the Costume Institute Gala, a Vogue-sponsored fundraising event for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute. The annual gala marks the opening of a new exhibit at the Costume Institute. The gala is famous for its star-studded attendance, lavish decorations, and its interesting themes, which guide the attire for the evening. Naturally, each year’s theme is the same as the Costume Institute's new exhibit. In 2016, the theme was Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology, an exploration of “how fashion designers are reconciling("Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology- Exhibition Overview"). The handmade and the machine-made in the creation of haute couture and avant-garde ready-to-wear” The exhibit featured nearly 200 hand and machine-made ensembles dating from the twentieth and twenty-first century. While the event lasted one night, and the exhibit only a few months, Manus x Machina created a lingering conversation about technology’s role in the history of fashion. To that end, the Met Gala is an event where some of the most wealthy people in the world gather in some of the most expensive, hand-crafted haute-couture creations in history. All of these factors raise important and often overlooked questions about the intersection of fashion, technology, and class. Because of this, it is interesting to explore these themes within the scope of the technological innovations of the nineteenth and twentieth century. In this essay, I will briefly explore an overview of the pre-nineteenth century fashion industry and its relationship to technology and class. Then, I will discuss the emergence of new garment technologies and their impact on the fashion market and class relations. Building on this, I will then investigate the coinciding development of the luxury fashion industry and the glorification of hand-made clothing. The emergence of the luxury fashion industry was a direct response to the democratization of clothing that resulted from innovations in mechanized-clothing production.

A Brief History of Garment Production before the mid 19th Century

A common misconception about the fashion industry prior to the mid-nineteenth century is that it functioned similarly to how the modern fashion industry operates today. While the concept of fashion has existed as long as humans have adorned themselves in clothing, the centralized fashion industry has only been around for a few centuries. Throughout much of history, the majority of people living in Western cultures have crafted their clothing at home. All parts of garment production — looming, weaving, and sewing — were carried out in the private sphere. While men were often in charge of leatherworking, most garments were made by women (Cowan, 26). Up until the advent of the industrial revolution in the late 18th century, western cultures “used tools dating back to biblical times” to produce clothes (Strasser, 126). This lack of innovation meant that average individuals were tasked with all parts of clothing production including “shearing their sheep, carding their wool, harvesting, soaking, pounding, and combing their flax producing long parallel fibers that could be spun”(Strasser, 126). After these laborious tasks, women were then responsible for using spinning wheels, or more expensive looms, to spin fibers into wool or linen cloth that could be sewn into garments (Strasser, 126). Even when the construction of a garment was completed, it would often need repairs. For this reason, hand sewing was largely considered to be the primary task for women in clothing production. In an 1838 edition of The Young Lady's Friend, Eliza Farrar wrote, “A woman who does not know how to sew is as deficient in her education as a man who cannot write" (New-York Historical Society). For this reason, women of all classes sewed, and the tradition continued with women teaching their daughters to sew. As illustrated in an 1850 account by Syracuse housewive Ellen Birdseye Wheaton, many women found the sewing tedious and never-ending:

“Since the second week, in March, I have been preparing garments, for children's summer wear, having shirts altered and made, for Charles [her husband], and having dresses made, and fixed till I am at times, almost bewildered. I began this work earlier than usual, this season, hoping much to get the main part of my sewing done, before the extreme heat of summer, but oh! it seems at times as tho' it could never be done” (Cowan, 64-65).

Wheaton is responsible for the construction, altering, and mending of all the clothes for her family, and clearly finds the work to be exhausting. However, she does not challenge the expectation that this was her role in the home. As evidenced by Wheaton’s sentiments, the making of clothing was just another household chore. Considering all parts of home clothing production, it is easy to see how time-consuming and arduous this task was. Therefore, it is safe to assume that a mid-nineteenth century lower to middle-class person did not have the privilege to concern themselves with the style of his or her clothes. Because garment construction was only one of the myriad tasks they had to complete on a day to day basis, the average person’s focus was more likely to be on the functionality of their clothing rather than how “in-style” it was.

While clothing production in the home was the reality for most, wealthier families would outsource the construction of garments to specialized artisans such as local mercers, tailors, and dressmakers. Rather than make their own garments from raw materials, the wealthy bought and imported fabric to be given to tailors. The wealthy would buy expensive woven silks, lace, tapestries, and fine embroideries from Italy and Lyon (Mikosch, 54). The textiles of the noble class were so expensive that, “Louis XV could easily spend over 16,000 livres on lace in a single month alone”(Mikosch, 54). Although artisans were responsible for the construction of the garments, the task of designing the garment was still up to the patron. Fashion was a “collaborative process” in which people provided their materials and cloth to tailors and dictated the styles they desired (Arnold, 25). Additionally, it was common for wealthier women to hire seamstresses to mend clothing that has torn or frayed (Strasser, 128). Because of the outsourcing of looming, construction, and mending, the upper class could focus on the design aspect of the garment-making process.

Therefore, wealthy people had time to think about their clothing designs and curate trends. Unlike today, trends were not introduced by certain fashion designers, as fashion designers were largely nonexistent prior to the mid-nineteenth century. Marie Antoinette's private dressmaker, or "ministre des modes," Rose Bertin was famous for her designs and can be considered the closest thing to a designer at the time. Although Bertin sold her dresses in shops, a common person could not buy a dress that was created in “close collaboration” for Marie Antoinette (McMahon). As evidenced by the fame of Rose Bertin, fashion trends prior to the mid-nineteenth century usually stemmed from royal courts. Throughout the 14th and 15th centuries, “the court of the Dukes of Burgundy was especially stylish” (Steele, 2). In the 16th century, Spain was one of the wealthiest countries and thus led to the trends of European fashion, with styles of high collars (Steele, 2). In the 17th century, under the reign of King Louis XIV, France became the leading fashion capital in the West. In fact, the 1690 Dictionaire Universal by Antoine Furetier included a new word “mode,” meaning “the manner of dressing following the customs of the Court” (Steele, 2). The opulent styles of the French court were famous for consistently introducing new trends for different seasons. In fact, King Louis XIV would keep track of court members’ attire to ensure they were not repeating the same outfit too frequently, and therefore embarrassing the court (English, Bonnie). The wealthy throughout Europe and America looked to French royalty for style inspiration. Because of this, fashion became a leading industry in France, causing Louis XIV’s minister of finance Jean-Baptiste Colbert to claim “fashion is to France what the goldmines in Peru are to Spain” (Qtd. in Steele,2). To capitalize on this status, the French promoted their fashion trends in many ways. Dolls were adorned in miniature versions of the current dresses of French royalty. These dolls were exported throughout the world, allowing for many countries to emulate their styles (Steele, 31). The doll’s garments were meticulously created, with careful stitching and beautiful draping (See Figure 1). These dolls served as a testament to the immense quality of the full-size garments. Additionally, styles were promoted in illustrations called fashion plates in a variety of publications. While the clothes of upper and working-class people were both hand-sewn, they differed greatly from one another. Upper-class clothing was luxurious and fashionable because it could afford to be so. Arguably, fashion only existed for wealthy people prior to the mid-nineteenth century, as they were the only people who could afford to keep up with trends. Because wealthy people outsourced their clothing, they were able to accumulate many different fashionable costumes that clearly differentiated them from the lower class.

The Emergence of new Garment Technologies and their Impact on the Fashion Market 1850-1950

As long as common clothing was produced in the home, the stark divisions between classes were clearly illustrated in a person’s outfit. This status quo began to face some challenges with the emergence of new garment-production technologies in the late 18th century. The first textile-producing machines emerged in England in the late 18th century. In 1767, James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny, the machine that allowed workers to spin many lines of cotton at once. By the 1770s, this invention “could operate 16 spindles at the same time, and, less than 15 years later, 80 spindles could be used” ("Spinning Jenny”). In 1769, the water frame, a water-powered loom, was invented by Richard Arkwrights. The water loom was followed by Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule in 1779, which once again simplified the cotton-spinning process. In 1785, Edmund Cartwright’s introduced the power loom and increased the profitability of textile production by greatly reducing labor (Allen, 381–402). In addition to these mechanized looms, technological advancements were created to help expedite the collection of raw materials like cotton. In 1794, the cotton gin was invented by Eli Whitney, making the collection of cotton faster by separating “cotton fibers from the seed boll” (“Cotton gin”). Due to this innovation, slavery usage in the United States doubled in size, lead to an excess of cotton production (“Cotton gin”). At this time, Whitney's machine and England’s new inventions revolutionized the cloth-making process. These innovations allowed England to produce finished textiles at a much faster rate, and sell these finished goods for a hefty price tag. As England was dependent on America for cotton, the English kept the designs for these new machines a secret (Strasser, 128). Despite these efforts from the British, the designs made their way to America where they prompted Samuel Slater’s Rhode Island Spinning Mill in 1790 (Strasser, 128). Initially, these mills operated using the putting-out system and generally employed women and children. Slater’s Mill was soon followed by Francis Cabot Lowell in 1814, who moved towards a wage-based factory environment (Strasser, 129). The Lowell Mills mass produced textiles and employed over 8,000 women. These women would work 13 hour days, 6 days a week, making about $3.25 a week (Wayne,118). As evidence by Lowell Mills, these inventions rapidly changed the landscape of the textile-making industry. Soon, most homes were purchasing textiles rather than spinning them in their own home because it was easier to do so. Despite this outsourcing of textiles, clothing construction was still largely done in the home in the first half of the nineteenth century.

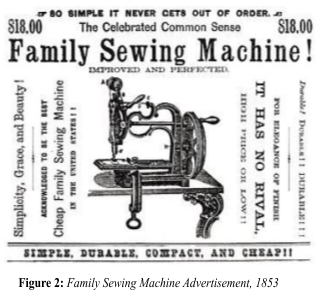

While the numerous textile-producing machines helped to expand clothing production in the late 18th century, no technology disrupted the landscape of the garment industry more than the sewing machine. The sewing machine was independently created by both “Walter Hunt (in 1834) and Elias Howe, who patented his machine in 1846” ("Sewing Machine”). Because Howe patented his invention, he is largely credited as the inventor of the sewing machine ("Sewing Machine”). However, in 1851, Isaac Singer patented his own factory sewing machine and has also become associated with the origin of the machine (Strasser, 128). Shoemakers immediately recognized the benefit of sewing machines for their craft and they were some of the first manufacturers to adopt the machine. Other clothing manufacturers followed suit and by 1862, “two-thirds of the sewing machines in America served manufactures inside shops” (Strasser, 128). Because the sewing machine was brand new, it was expensive and the average person could not purchase one for their home. An 1853 family sewing machine advertisement boasts the price of $18.00, which in that time was about $590, well out of the reach of the average working-class person (See Figure 2). Many seamstresses and tailors were afraid that sewing machines would put them in business. In fact, in 1831 tailors broke into inventor Barthelemy Thimonnier factory and, in Luddite fashion, broke his early sewing machines (Green, 34). Other seamstresses used them to their advantage, buying them, and selling their finished products to manufacturers (Strasser, 138).

This sewing machine putting-out system was brief. Manufacturers realized they could have greater control over their workers in a new labor area: the sweatshop. Sweatshops, small and cramped workspaces with poor conditions, arose in urban areas, especially in Britain and the United States. During the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, sweatshops were filled with immigrants and people from rural areas who flocked to cities in hope of better wages (Powell, 113). Early sewing machines “made it possible for each tailor or seamstress to increase production ten to fifteen times,” expediting the rate at which clothes could be made (Cowan, 73). This mass-production created a demand for ready-made products. Technological advancements like the power loom, sewing machine, and the sweatshop “destroyed the cottage mode and created large-scale technological unemployment for the first time,” forcing laborers to work in sweatshops (Allen, 381–402). To fulfill these high demands, conditions were poor for sweatshop laborers. It was common in sweatshops for workers to work “sixteen hours a day, six days per week” cramped hazardous spaces (Powell, 113). These conditions are best exemplified by the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 that killed dozens of women. Sweatshops emerged to fulfill the demand for ready made-products in the wake of the sewing machines.

The first signs of this shift to the ready-to-wear economy were seen in the wake of the war of 1812, when garments were uniformly cut by the United States Army and distributed to tailors to be adjusted, to create a singular look (Hollander, Anne). This wartime call for uniform standardization continued in the Civil War and spurred on the popularization of the sewing machine. Wartime demands called for high quantities of identical uniforms that sewing machines could help to create. In 1861, at the beginning of the war, the Union army had 74 sewing machine manufacturers and the Confederate army had none (Breakwell, 100). As tailors left for the front lines, women were pressured to purchase sewing machines to help with the war effort. In 1861, United States Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs directly called for war suppliers to “set the innumerable needles and sewing machines at [their] command to work” to help the thousands of troops that “wait for clothes to take the field” (Breakwell, 100). To help facilitate the construction of uniforms, standard clothing sizes for men were created from statistical data gathered from Union soldiers (Cowan, 73). Popular opinion shifted to favor the sewing machine, as it became viewed as a war advantage rather than a career-threatening machine. This acceptance of the sewing machine and standardization of men’s clothing continued after the war, drastically changing menswear in Europe and North America. By the 1870s, thanks to the influence of the Civil War and the subsequent rise of sweatshops, it was “possible for any man or boy, from any walk of life, to obtain, at a reasonable cost, a well-fitting suit of clothes” at shops or through mail-ordered services (Cowan, 73). Although ready-made clothes in the late nineteenth century often fit poorly and needed to be altered, they quickly became a viable option for middle and working class men in the West. Department stores began to emerge to meet this new demand. The French department store chain Dewatcher Frères advertised boasted “Vêtement Confectionnés,” or “made clothing,” for men in their advertisements (See Figure 3). While this may seem odd now, pre-made clothing was a revolutionary idea and a selling point for retailers.

Because of its roots in the army, ready-made clothing was initially only available for men. Women could buy accessories items such as “cloaks, shawls, and mantuas” that could be generally sized to fit most women (Cowan, 73). Because sewing and clothing construction were traditionally women's chores, the shift to ready-made women’s clothing took longer, as women were still expected to make clothes in the home. However, as ready-to-wear manufacturers grew and styles changed, eventually womenswear began to emerge on the market. At the turn of the 20th century, women’s clothing was increasingly inspired by menswear, culminating in the two-piece outfit that came into fashion for women. The style consisted of a skirt and a button-down blouse called a shirtwaist. The style was popularized by “Gibson Girls,” stylish illustrations of women found in magazines and newspapers (See Figure 4) (Cowan, 75). Shirtwaists resembled men’s shirts and were naturally some of the first womenswear items to be mass-produced, while more feminine skirts and dresses were still made in the home. Advertisements for shirtwaists boasted new styles for prices as low as $1. Women of all backgrounds could participate in the “Gibson Girl” trend because of the accessible shirtwaist price tag. By 1910, nearly all women’s garments were being manufactured at “prices suitable for everyone from the poorest farm girl to the richest society matron” (Cowan, 75). Women’s clothing soon began to take over catalog advertisements and window space in department stores. Eventually, women’s clothing, which was valued at “less than one-third of that of men in 1890 skyrocketed to almost half a billion dollars, twenty million more than men’s wear, by 1914” (Cowan, 144). Ready-to-wear clothing for women was furthered in 1941 when a "scientific study of body measurements" was conducted by the Work Projects Administration to improve the fit of women's garments (O'Brien, Ruth). The WPA measured over 10,000 women to create standard clothing sizes for women (O'Brien, Ruth). By the early 1900s, people grew to rely more and more on ready-made clothing as production increased and prices dropped. The wage-labor economy made purchasing clothes the most viable option; gone were the days of crafting clothes from scratch.

Initially, the public reception to ready-made clothing was lukewarm. People thought that sewing machine clothing was not as “durable” as handmade clothing (Breakwell, 100). This was because early sewing machines were not very effective. Initial hand-powered sewing machines could only sew 20 stitches per minute in 1870, and oftentimes it was admittedly not the best quality (Green, 37). However, by the beginning of the twentieth century, steam and electric powered machines could sew over 200 stitches a minute (Green, 37). By 1950, an average sewing machine could perform up to 4,500 stitches per minute (Green, 37). As technology improved, so did the quality of the sewing machine stitching, and in turn, ready-to-wear clothing improved as well. The public’s newfound appreciation of ready-made clothing is best exemplified by an 1859 New York Tribune article that foreshadowed what was to come:

“The needle will soon be consigned to oblivion, like the wheel, the loom, and the knitting-needles. The working woman will now work fewer hours, and receive greater remuneration. People will . . . dress better, change oftener, and altogether grow better looking. The more work can be done, the cheaper it can be done by means of machines — the greater will be the demand. Men and women will disdain the soupcon of a nice worn garment, and gradually we shall become a nation without a spot or a blemish” (New York Tribune, c. 1859, quoted Qtd in Mendelsohn, Adam, 189)

At the beginning of the 20th century, ready-to-wear clothing was a “booming enterprise in the United States,” estimated to be worth over $817 million (Cowan, 79). The ultimate adoption of “half a million sewing machines world-wide in 1871 (from just over 2,000 in 1853) contributed towards the rapid fall in the price of clothing, a huge increase in the scale of operations in the garment trades” (Breward, 54). Ready-made clothing democratized the fashion world as it was advertised to be “for everyone from farmers to travelers, from mourners to children, and from firemen to whalemen” (Green, 22). Additionally, ready-made clothing was thought to have made “art through clothing...possible for everyone” f(Green, 25). Because of this “democratization” of fashion, clothing no longer clearly distinguished class. The playing field of fashion was leveled, and people now had the opportunity to experience fashion trends. Style was no longer the strong signifier of class.

Development of Luxury Fashion and the Glorification of Hand-Made Clothing 1850-1950

The new garment technologies of the 19th century — the power loom, the sewing machine, the sweatshop, the sizing chart — all helped bring fashion to the average person in Europe and North America. Now earning wages, working-class people no longer had to construct their own garments and were able to buy clothes and participate in fashion trends. By the 20th century, the style of a person’s outfit could no longer convey a person’s wealth. However, as many economic and cultural researchers have theorized, when “lower social class groups attempt to emulate the tastes of higher groups, this causes the later to respond by adopting new tastes that will re-establish and maintain the original distance” (English, 7). Therefore, it is interesting to explore the emergence of Haute Couture at the same time as ready-made clothing. Haute Couture became a counter-movement for the rich in response to the ready-to-wear movement. Haute Couture was comprised of custom luxury garments known for their “fine fabric, sumptuous embellished with layer of either lace or tulle, with hand embroidery and beading”(English, 8). The term Haute Couture can be translated to mean “high sewing,” promoting the art of luxury hand sewing. Haute Couture glorifies the hand-made, one-of-a-kind uniqueness of a garment, making Haute Couture pieces entirely opposite to ready-to-wear clothes.

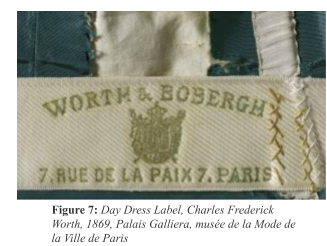

Naturally, Haute Couture was birthed during the second half of the nineteenth century in Paris, France, the reigning luxury fashion capital of the West. The creation of Haute Couture is largely attributed to Charles Frederick Worth, an English-born designer. Worth began his career in France in 1845 as a professional dressmaker (Krick, Jessa). Worth became known for his “use of lavish fabrics and trimmings”(Krick, Jessa). He began to design for famous clients, including the royal Princess de Metternich (English, 9), Empress Eugénie of France, and Empress Elisabeth of Austria (Lagasse, Paul). However, unlike the dressmakers of the royal courts in the preceding centuries, Worth served a “broader clientele” (English, 9). Worth’s other famous clients included the wealthy American Rothschild and Vanderbilt families, as well as famous actresses of the time, such as Lillie Langtry (English, 9-10). Worth’s diverse clientele illustrates how Haute Couture served all of the upper class, not just those with a royal status, as it had been in centuries prior. Thanks to these wealthy clients, Worth became immensely popular and frequently featured in publications like Vogue. Worth created “seasonal presentations of his dresses to customers on live models" and would sell each dress as a one-of-a-kind, "like an artwork by a painter"(Rocamora,29). Admittedly, as “Haute Couture was founded in the same epoch in which the sewing machine was invented” (Martin,15), Worth used modern technology like sewing machines and standardized patterns (English, 24). Despite this, Worth was famous for the meticulous details of his hand-sewn embellishments, as they were what separated his work from the ready-to-wear garments of the masses. As seen in Figure 6, each embellishment was artistically placed and gowns were expertly crafted to precisely fit their patron’s body. Additionally, Worth also had “his signature sewn onto labels affixed to clothes,” a new concept at the time (English, 24). This label became a new defining factor of wealth in fashion (See Figure 7). For the first time, it became important in fashion to consider “who” you were wearing as couturiers became a “quixotic dictator[s] of trends” (Breward,52). It was common knowledge that the “price of a worth of dress started at 1,600 francs” (Breward,52). Therefore, a person’s wealth was immediately implied by wearing a Worth label. While middle and lower class people could replicate certain styles through ready-made clothing, they couldn’t replicate the Worth name.

Other designers followed the precedent set by Worth, and so the luxury fashion market grew. Designers like Jeanne Paquin and Paul Poiret opened fashion houses that outfitted clients in Haute Couture creations, making their names synonymous with luxury. However, in the wake of World War One and the Great Depression, Haute Couture could no longer solely exist in the same way it had previously, because “the lifestyles of the rich and fashionable were changing dramatically” (English, 37). Despite this, divisions between the wealthy and the middle or working classes were maintained through a spawn of Haute Couture: prêt-à-porter lines, or luxury ready-to-wear. Many of the couture designers such as Chanel, Lelong, and Patou began to produce less custom, but still luxurious, lines of clothing to remain viable in economically trying times. Gabrielle Chanel is often credited with the development of prêt-à-porter, with her inventions like the “little black dress” and tweed jackets, that were minimalist, non-custom, luxury garments. Chanel’s introduction and popularization of simple designer clothes were referred to as the “Pauvrete de luxe”, or “poor luxury” movement (English, 37). Despite its name, Pauvrete de luxe was just another way in which the wealthy maintained their status during times of economic struggle. A Chanel dress could “cost anywhere from 3,000 to 7,000 francs in 1915….in today’s money, $2,100” (Women of fashion, 42). An August 1922 edition of Harper's Bazaar claimed “Chanel has succeeded in making simplicity, costly simplicity, the keynote of fashion of the day” (Harper's Bazaar, August 1922). Designers like Madeleine Vionnet, Jeanne Lanvin, and Jane Regny created garments of a similar nature (Steele, 44). Pauvrete de luxe helped lead to the creation of popular styles like the flapper dress, which “coexisted in couture and ready-to-wear” (Richard and Koda, 24). While these garments used cheaper materials like rayon or jersey, the ethos of Haute Couture was still intact due to their brand name, allowing these prêt-à-porter garments to be markers of economic superiority. By the end of world war two, western economies started to recover and more luxurious styles came back into fashion. In 1947, Christian Dior’s “New Look” that “applied drapery with the fullness of the Baroque” came into fashion and marked “the privileged return of copious textile” for luxury consumers (Martin, 13). Because of these fluctuating economics times in the first half of the twentieth century, fashion houses had both Haute Couture and prêt-à-porter lines to help their upper-class consumers differentiate themselves.

Luxury fashion’s resilience when faced with mechanized clothing production and economic troubles is a testament to the lengths that the upper class will go to distinguish themselves from lower classes. This economic distinction was rooted in the distinctions of fashion in prior centuries as “the couture customer from the 1870s to the 1950s was encouraged to believe that she was the direct decedents of those Ancien Regime exquisites who first patronized the tradition" (Breward, 50). As a Paquin dress would’ve cost more than a year’s wages for the average person in 1938, “high fashion maintained a monopoly on the concept of desirability” (Breward, 52). The initial shift back to hand-sewn clothing by the wealthy in the wake of new technologies is clear evidence of a class shift.

Conclusion

The emergence of a centralized luxury fashion industry is rarely discussed as a response to new garment technologies. However, I believe there was a clear correlation between the development of ready-to-wear garments and the development of luxury fashion houses. Over the course of a century, designer brands, rather than styles, became the new marker of economic prosperity and class division in the West. This overarching shift in the world of fashion provides us with greater cultural insight to the societies of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Europe and North America.

Bibliography:

Allen, Robert C. “The hand-loom weaver and the power loom: a Schumpeterian perspective”, European Review of Economic History, Volume 22, Issue 4, November 2018, Pages 381–402,

Arnold, Rebecca. Fashion: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central, 25

Breakwell, Amy “A Nation in Extremity: Sewing Machines and the

American Civil War,” Textile History and the Military. Leeds, U.K.: Maney Publishing, 2010.

Breward, Christopher, Fashion, OUP Oxford, 2003

“Cotton Gin." In The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, edited by Helicon. Helicon, 2018. http://ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/login?

Cowan, Ruth Schwartz. More Work for Mother: The Ironies of Household Technology from the Open Hearth to the Microwave. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2008.

English, Bonnie. A Cultural History of Fashion in the Twentieth Century: From the Catwalk to the Sidewalk. Oxford: Berg, 2007.

"Exhibitions." Home Sewn: Three Centuries Of Stitching History | New-York Historical Society. Accessed May 08, 2019. http://m.nyhistory.org/exhibition/home-sewn-three-centuries-stitching-history.

Green, Nancy L. Ready-to-wear and Ready-to-work: A Century of Industry and Immigrants in Paris and New York. Durham: Duke University Press, 1997.

Harper's Bazaar, August 1922

Hollander, Anne. "The Modernization of Fashion." Design Quarterly, no. 154 (1992):

Honeyman, Katrina, Marie-Louise Nosch, and Kjeld Galster. Textile History and the Military. Leeds, U.K.: Maney Publishing, 2010.

Krick, Jessa. “Charles Frederick Worth (1825–1895) and the House of Worth.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/wrth/hd_wrth.htm (October 2004)

Lagasse, Paul, "Worth, Charles Frederick." In The Columbia Encyclopedia, 8th ed. Columbia University Press, 2018.

"Manus X Machina:Fashion in an Age of Technology Exhibition Overview,." Metmuseum.org. Accessed May 08, 2019. https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2016/manus-x-machina.

Martin, Richard, Harold Koda, John P. O’Neill, and Barbara Cavaliere. Christian Dior: , The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1996.

McMahon, Elizabeth, and Lourdes Font. 2009 "Bertin, Rose." Grove Art Online. 8 May. 2019

Mendelsohn, Adam. The Rag Race: How Jews Sewed Their Way to Success in America and the British Empire. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Mikosch, Elisabeth, "The Manufacture And Trade Of Luxury Textiles In The Age Of Mercantilism" (1990). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings

O'Brien, Ruth, Women's measurements for garment and pattern construction, Washington, D.C. : U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1941

Powell, Benjamin. “A History of Sweatshops, 1780–2010.” Chapter. In Out of Poverty: Sweatshops in the Global Economy, 112–26. Cambridge Studies in Economics, Choice, and Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014 113

Robert C Allen, The hand-loom weaver and the power loom: a Schumpeterian perspective, European Review of Economic History, Volume 22, Issue 4, November 2018, Pages 381–402,

Rocamora, Agnès. Fashioning the City: Paris, Fashion and the Media. London: I.B. Tauris, 2009.

"Sewing Machine." In The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, edited by Helicon. Helicon, 2018.

Steele, Valerie. Women of Fashion: Twentieth-century Designers. New York: Rizzoli International, 1991.

Steele, Valerie. Paris Fashion: A Cultural History. Oxford: Berg, 1998.

Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. New York: H. Holt, 2000.

“Spinning Jenny." In The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, edited by Helicon. Helicon, 2018.

Wayne, Tiffany K, Women's Rights in the United States : A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Issues, Events, and People, ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2014.

"Women's Measurements for Garment and Pattern Construction : O'Brien, Ruth, B. 1892 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming." Internet Archive. January 01, 1970. Accessed May 08, 2019. https://archive.org/details/womensmeasuremen454obri/page/46.